We're excited to share some insights into the thought processes of our composers and visual artists with our new blog. We'll be sharing ideas, sounds, and images as we lead up to our show on August 31st at the Theatre at The Ace Hotel. Next up, we have Nathan Johnson.

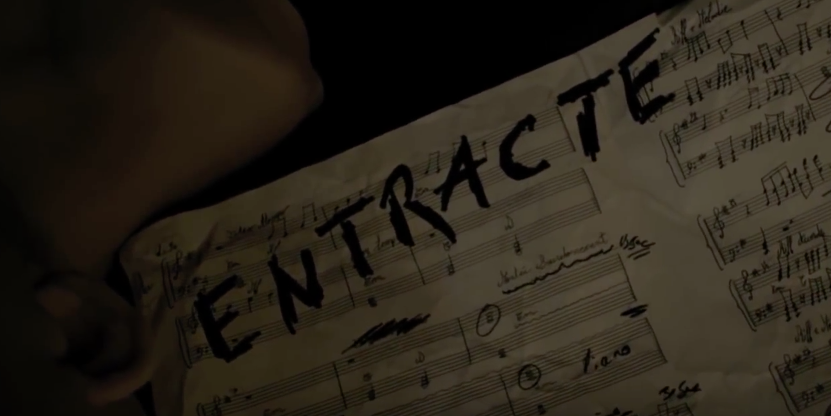

I love musical interludes … those little moments that give us space to breathe, while somehow tying broader themes together. In theatrical productions, these entr’actes (literally, “between the acts”) were originally short pieces of music or dialogue used to distract audiences from set changes happening behind closed curtains. The interludes would serve as bridges between the main events of a story by expanding on motifs, creating tonal shifts, and sometimes even developing self-contained plots of their own.

I’m always intrigued by art forms that emerge from technical restrictions, and history is rich with examples. The average length of recorded music was defined and restricted by the medium that held it; likewise, the vision of a film by the aspect ratio of its frame. In the world of comics, many newspaper editors made a practice of removing the top row of panels from nationally syndicated strips as a response to space restrictions. This forced cartoonists to empty their headers of everything except a title since they knew it would be omitted for many of their readers, but Calvin & Hobbes cartoonist Bill Watterson used the extra space to draw self-contained preludes. These served to introduce the theme of the story, and, in many cases, they were as enjoyable as the entire comic.

As Brian Eno points out in his book, A Year With Swollen Appendices, “Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit – all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.”

This is the nature of how forms develop. In the case of the interlude, a technical restriction gave birth to an artistic solution that continued on, even as the original restriction ceased to exist.

There’s absolutely no technical reason for an interlude in a movie, but we still occasionally see them used to great artistic effect. I’d be hard-pressed to find a scene in a recent film that made me smile as much as the boisterous accordion entr'acte from Leos Carax’s Holy Motors.

Likewise, I was astonished and thrilled by the left turn P.T. Anderson takes in Magnolia where, for a brief moment, the camera finds the main characters spread across Los Angeles and inexplicably singing the same song. The music isn’t diegetic, and Anderson makes sure you’re not confused about this, as the song never feels like it’s coming from a record player or a car stereo in the scene. It’s just there, maybe in the atmosphere. The characters simply sing along with the disembodied voice of Aimee Mann, and the scene is unexpectedly magical and heartbreaking.

With the Echo Society shows, we’ve never had a technical reason to consider interludes since we’re not changing scenes, but as I began thinking about our upcoming show, I started getting excited about writing a handful of smaller “linking pieces” that could weave through the entire night.

Our shows are, by nature, fairly modular. In the past, we’ve begun our preparation by choosing a common theme (“Bloom” or “Veils,” for instance), but we’ve been pretty isolated in our writing, sometimes not hearing the other compositions until the first rehearsal.

This show will be different for a number of reasons, but one key shift is that we’re focusing more on the night as a whole. Usually, our musical director, Joe, waits to sequence the show until all the pieces are complete, but this time we wanted to take a different approach. So, three months ago, we gathered around Rob’s dining room table and started sketching out the arc of the whole evening before a single note was written.

We plotted out dynamic levels, transitions, and instrumentation changes, and then met up repeatedly over the following months to share our progress. We’re now thinking further outside of our own compositions and digging for ways to create a more unified experience that represents the title of our fifth show: V.

In our first blog post, Ben noted that “V” is a representation of Spirit (I) into Matter (IV). For my interludes, I’ve been exploring this theme specifically as it relates to “Breath.” We see it expressed in the creation story of the world’s major religions: a divine being shapes matter (the dust of the earth) and then breathes into it “the breath of life.”

Breath is, of course, the thing that sustains us, but it also empowers a unique voice, both literally and metaphorically. This is one of the things that has been so inspiring about working with the composers in the Echo Society. Each show reminds me of the variety of voices being expressed, from Jud’s cinematic melodicism to Jeremy’s electronically-generated pattern work.

Preparing for this show has been especially fun for me, because I’ve had the opportunity to peek into what makes each of the other compositions tick, and then think about ways to bridge the gaps between them. In some cases, this involves playing around with keys and timing, often calling the other composers to float ideas about how I might interpret pieces from their work. If you look at my writing session, it’s actually laid out sequentially like a film, with the other compositions abutting and overlapping my files for context. In the photo above, you can see individual pink snippets from Brendan's piece that that he sent over for me to incorporate into one of my compositions. In this way, I’m quoting, referencing, and repurposing other elements in order to tie these voices together.

And this brings me back to our overarching theme for the night. In writing interludes, I’m operating in the spaces between the acts, looking for a common thread to connect the dots. I decided early in my process to feature an actual voice, so I’ve been working with my frequent collaborator (and one of my personal favorite voices), Katie Chastain. Each interlude has developed into a sort of meditation on breath, and I’m reminded that although air is, essentially, unlimited, our breaths are not. I almost imagine the voice in these interludes as a spirit of the theater; a spectral observer from a forgotten time, reminding us that we have the opportunity to use our breaths – our lives – to create something unique.

- Nathan